In May 1945, several senior Gestapo officials made their way to Dahme, Schleswig-Holstein (northern Germany on the Bay of Lübeck) to prevent their arrest by the Allies. Officials at the British Field Security Post in Lübeck learned about these men and their hiding place from a captured Gestapo man. Immediately, British military police drove 31 miles to the Strandhotel and arrested five former Gestapo men ⏤ two officers and three NCOs. Taken back to Lübeck, the prisoners were turned over for interrogation at the city’s Marstall prison.

One of those men was SS-Sturmbannführer and Kriminaldirektor, Horst Kopkow. At the time of his arrest, Kopkow was a relatively unknown Gestapo official but as time went on and the British interrogated former Gestapo men, Kopkow’s name kept being brought up. It turned out he was the department chief responsible for counterintelligence (i.e., arresting foreign agents), the German radio program known as “Funkspiel,” and well-regarded by his superiors for his knowledge of Soviet espionage.

After extensive official and unofficial investigations, it became clear that Kopkow was personally responsible for sanctioning the torture and ordering the executions of foreign agents of MI6 and the British-led Special Operations Executive (SOE). I’ve written before about Hitler’s “enablers” (click here to read the blog, Hitler’s Enablers – Part One – Wannsee Conference and here for Hitler’s Enablers – Part Two – The Camps). Kopkow was an enabler but as Stephen Tyas points out in his book (see below), the Gestapo chief was a “desktop murderer.” He never personally pulled the trigger or hanged a prisoner, but he signed the Sonder behandlung, or “Special treatment” orders from his Berlin desk. In the end, he escaped justice because of the protection provided by British Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), or MI6.

Did You Know?

Did you know that one individual was responsible for preparing France for the invasion of Normandy (i.e., D-Day)? During World War II, Jean-Louis Crémieux-Brilhac (1917−2015) served as Gen. de Gaulle’s propaganda chief. As the preparations for the Normandy invasion intensified during early 1944, M. Crémieux-Brilhac was assigned the responsibility for telling French citizens how to react once the inevitable invasion took place and efforts to liberate France began. He was secretary of the Free French Propaganda Committee, and he drew up four pages of instructions to “all French men and women not organized in, or attached to, a Resistance group.” Those instructions were handed over to the French service of the BBC. Separate orders were drawn up for broadcast to members of the Maquis. (These were the famous “personal” messages read out on the BBC in advance of the invasion ⏤ click here to read the blog, Dah-Dah-Dah-Duh.)

Crémieux-Brilhac’s messages were directed to the population in general as well as specific instructions to mayors, police, factory workers, etc. The biggest disagreement about the “call-to-arms” was between the Communists and the Gaullists. Communist resistance fighters were very influential in the French Resistance, and they demanded an all-out insurrection (i.e., general worker strikes and armed insurrection) on the eventual day of the invasion. M. Crémieux-Brilhac and the majority resisted the Communists’ demands and the majority won.

The instructions to the French were that “all French must consider themselves as engaged in the total war against the invader in order to liberate their homeland.” He made it clear that the French were to consider themselves “all soldiers under orders” and “Every Frenchman who is not, or not yet, a fighter must consider himself an auxiliary to the fighters.” Citizens living within the Normandy combat zone were instructed to “disrupt using all means transport, transmissions, and communications of the Germans.”

After liberation, the original instruction documents were retained by M. Crémieux-Brilhac. Upon his death in 2015, the papers were donated to the French National Archives.

Let’s Meet Horst Kopkow

Horst Kopkow (1910−1996) was born in East Prussia, Germany (now Poland) as the sixth child of a businessman and hotel owner. His childhood city, Allenstein, was overrun by the Russian army during the first world war and two of his older brothers died in the trenches on the French battlefields. These memories heavily influenced his vision of Russia and later, the Soviet Union with Kopkow vowing to fight Communism the rest of his life.

He was not a good student and in 1928, left school to begin an apprenticeship in a pharmacy (i.e., drugstore). Kopkow successfully passed his pharmacist examination in 1931 and was hired by the pharmacy during a time of high unemployment in Germany. It was a period when the Nazi party was on the rise with its promises to fight inflation, provide jobs, return the country to its former glory, and for Kopkow, the most important promise: to fight Communism.

While working for the Gestapo in Allenstein in 1936, Kopkow met and married a local woman employed by the Nazi women’s movement (i.e., Bund des Deutschen Mädchen). Gerda Lindenau (1911-date unknown) was a fervent Nazi who fully supported her husband’s Nazi activities and did not repent her position even after the war ended. (Decades later, Gerda finally acknowledged her beliefs were wrong.)

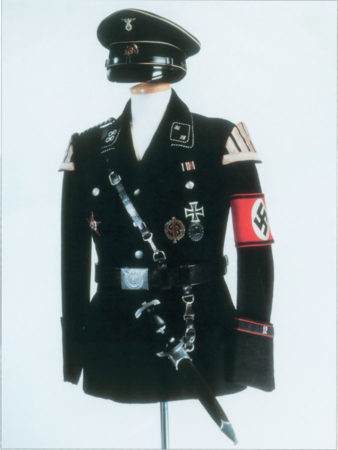

National Socialist German Workers’ Party

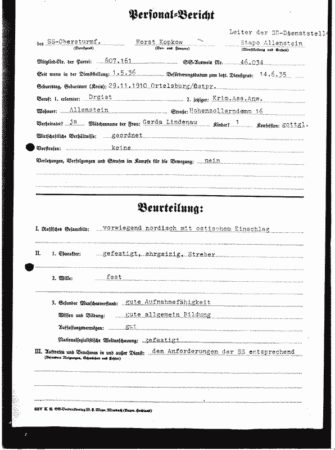

Founded in 1920 by Adolf Hitler, the National Socialist German Workers’ Party, or the Nazi party was a far-rightwing nationalist political party. On 7 May 1931, Kopkow joined the Sturmabteilung (SA), or the “Brownshirts” (the paramilitary arm of the Nazi party) and two months later, he became Nazi member no 607,161. The SA was a bunch of thugs and Kopkow was always at the front when fights between Communists and Nazi party members broke out. His zealousness and fearlessness in “battle” caught the eyes of senior Nazi party members and soon, Kopkow was asked to take a paid political position within the party. He declined several times since working at the pharmacy paid much better. Instead, Kopkow resigned from the SA in August 1932 and immediately joined the “Black Shirts,” or the Schutzstaffel (SS) which at the time were Hitler’s personal bodyguards. His low SS number (46,034) meant Kopkow was considered to be an elite “Black Shirt” member. Kopkow was assigned to Unit 61 SS-Standarte in Allenstein where he became one of its leaders. By 1934, Kopkow took a full-time job with the SS and accepted a position with the newly created Geheime Staatspolizei, or Gestapo.

R.S.H.A. Promotions

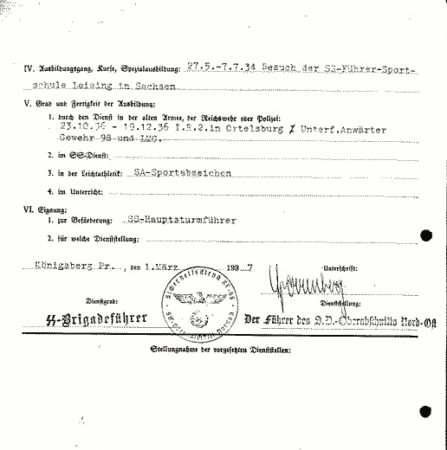

Kopkow rapidly rose in rank within the Reichssicherheitshauptamt (RSHA), or the Reich Security Main Office (i.e., German security forces). His first promotion came shortly after joining the Gestapo when he became a SS-Obertruppführer, or sergeant and within two months, Kopkow was promoted to SS-Untersturmführer (lieutenant). Clearly, Kopkow was a rising star and in May 1934, he was sent to officer training school where he excelled. Afterward, Kopkow returned to the Allenstein Gestapo office where he began work in the counter-espionage department. Staying in Allenstein, Kopkow was promoted once again in June 1935 to SS-Obersturmführer (first lieutenant). It was during this period that Kopkow learned the interrogation techniques he would use in his future Berlin role.

Kopkow was promoted once more in April 1937 to SS-Hauptsturmführer (captain) and after years of training, one last and most important training course remained. Kopkow attended the nine-month Führerschule der Sicherheitspolizei und des SD, or “Security Police and SD Officer Training School” in Berlin (Schloss Straße 1, Berlin-Charlottenburg). After successfully completing this training, Kopkow was promoted to Kriminalkommissar and began his new assignment in the national Gestapo headquarters at Prinz Albrechtstraße 8 in Berlin.

The Gestapo

The RSHA was structured with seven divisions (departments) called Amter (plural) or Amt (singular). Amt IV was the “Suppression of Opposition.” Known as the Geheime Staatspolizei, the Gestapo was responsible for repressive measures and the search for opponents of the Third Reich. Led by SS-Oberführer Heinrich Müller, Amt IV was further divided into six sub-divisions with Amt IV A2 responsible for counterespionage and counter-sabotage. Amt VI was the “Foreign Intelligence Service,” or the Sicherheitsdienst (SD) ⏤ the Nazi party intelligence service ⏤ and the two RSHA departments worked together closely in Germany and the occupied countries to identify and arrest foreign agents.

Kopkow’s first assignment in September 1938 was in the administrative department where he investigated and interrogated returning Germans from the Soviet Union. Kopkow’s expertise in the Soviet Union led to his participation with a senior German delegation to Moscow in September 1939 as Hitler’s minister of foreign affairs, Joachim von Ribbentrop (1893−1946)) negotiated an amendment to the German-Soviet agreement signed a month earlier. After this mission and his return to Berlin, Kopkow was assigned to another sub-department and shortly afterward, the Gestapo was re-structured and SS-Obergruppenführer Reinhard Heydrich was named to lead the overall Reich security forces. Kopkow became the acting department chief of Amt IV A2 in July 1940 and by March 1941, was listed as the department chief. Kopkow was the youngest chief in the organization. He was responsible for investigating acts of sabotage, identifying and arresting foreign agents, fraudulent documents, and running the Gestapo’s Funkspiel, or “Radio Games.”

Over time, Kopkow’s reputation was enhanced by his success in disabling the SEO primarily through Funkspiel with the resultant capture of its agents in many of the occupied countries. He was also instrumental in breaking up the Soviet espionage units known as the Rote Kappelle, or “Red Orchestra” and the Rote Drei, or “Red Three.” After the 20 July (1944) plot to assassinate Hitler, Kopkow was assigned to investigate and identify the perpetrators. As a result, about five thousand people were executed on orders from Hitler.

Special Operations Executive

The British-led SOE placed its agents inside the occupied countries for the purpose of gathering intelligence, sabotage, and supporting local resistance groups. They went in as teams of three including a radio operator. Many of the agents were women who acted as a team’s courier or as the wireless operator. (Click here to read the blog, Women Agents of the SOE.) Through Funkspiel, Kopkow’s agents were able to capture the wireless operators and use their radios to fool the SOE in London. Kopkow and his men were successful breaking the SOE circuits and capturing many of its agents. He decimated the SOE circuits in Holland (“N” Section) and France (“F” Section) didn’t fare much better. F Section circuits such as Prosper, Juggler, and Clergyman were betrayed and many agents were arrested, interrogated, and tortured. Hitler signed two decrees, the Commando Order and Nacht und Nebel which essentially were death decrees for captured foreign agents (click here to read the blog, Hitler’s Commando Order and here to read Night and Fog). Evidence indicates that Kopkow signed off on the “Special treatment” orders for the execution of any foreign agent.

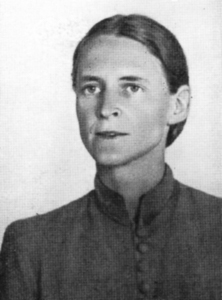

It has been estimated that Kopkow was responsible for ordering the deaths of between two hundred and three hundred Allied agents including Violette Szabó, Noor Inayat Khan, Francis Suttill, Robert Benoist, Denise Bloch, Andrée Borrel, Vera Leigh, and Frederick Grover-Williams (click here to read the blog, The Racer, the Spy and the Erotic Model). Vera Atkins (1908−2000) of “F” Section was responsible for tracking down the fates of her SOE women agents and in the process, uncovered much of Kopkow’s responsibility for their deaths.

Die Rote Kapelle

One of Kopkow’s significant achievements was breaking up Die Rote Kapelle, or “The Red Orchestra” (click here to read the blog, Die Rote Kapelle). It was an anti-Nazi organization comprised loosely of various resistance networks including the Lucy spy ring, the Trepper Group, and the Schulze-Boysen/Harnack Group. By monitoring radio transmissions (part of the “Funkspiel” program), the Gestapo traced the information back to Trepper’s Belgian headquarters and arrested one of the resistance members. He told his interrogators everything and soon, the Gestapo had the network’s code book. Mass arrests took place, and the leaders were executed at Plötzensee prison along with Mildred Harnack, the only American woman executed by the Nazis.

Rote Drei, or “Red Three” was a Red Army military intelligence operation and consisted of three clandestine radio stations operating out of Switzerland. It was led by Alexander Radó, a Hungarian communist. Although linked to British intelligence, the information it gathered was sent to the Soviet Union. It was Kopkow’s experience with this secret underground radio network that he used later to help leverage a job with the British SIS.

The Strange Case of Frank Chamier

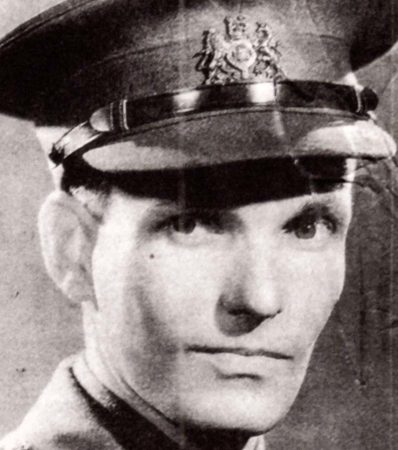

Kopkow was a pretty calm, cool, and collected prisoner while being interrogated. However, there was one session in which he lost his composure. His interrogator wanted information about the fate of Major Frank Chamier (1909−c.1945).

Major Chamier was a MI6 agent sent to Germany in April 1944 with his wireless operator, Frederick Wilhelm Reschke. (Reschke was a Wehrmacht deserter whom MI6 plucked out of a British POW camp and trained as a field agent.) After parachuting into German near Stuttgart, Chamier was betrayed by Reschke to the local police.

The two men were taken to Berlin where they were turned over to the Gestapo and interrogated. Chamier eventually ended up in the hands of Amt IV A2 and Kopkow. Chamier was to be used in Kopkow’s successful “Funkspiel” program. However, the Germans needed the security codes which only Chamier knew. He was likely brutally beaten and tortured by Kopkow’s men to obtain the codes. Evidence supports the fact Chamier did not divulge anything.

Under British interrogation, Kopkow admitted remembering Chamier and confirmed the major was held at Amt IV A2 for questioning. He also indicated being present for part of Chamier’s interrogation and that the British agent cooperated. However, Kopkow denied any knowledge of the treatment given Chamier and that the prisoner had died in an Allied bombing raid on Berlin. Kopkow’s interrogators did not believe him and were convinced he was lying about Chamier’s treatment and fate.

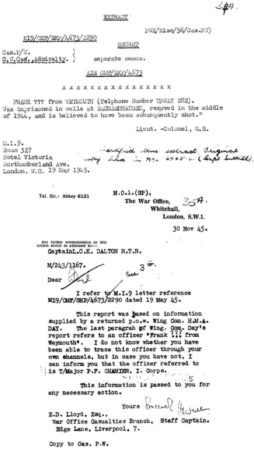

After the war ended, several investigations led to the conclusion Chamier had likely died either as a result of torture or execution in a concentration camp. One of the strongest pieces of evidence came from a debriefing of Wing Commander H.M.A. Day (1898−1977) after he had been liberated from KZ Sachsenhausen. (Commander Day was one of the escapees from Stalag Luft III ⏤ immortalized in the film, “The Great Escape.”) He said a Sachsenhausen prisoner by the name of Frank from Weymouth had identified himself as “Upway 282” (Chamier’s home telephone number) but Frank was transferred from Sachsenhausen in midsummer 1944. A former KZ Ravensbrück inmate testified about a British major arriving in the summer of 1944 and identifying himself as Upway 282. A captured Gestapo man stated Chamier had been betrayed by his German companion and the MI6 agent died from the effects of torture that Kopkow had ordered.

The official MI9 version of Chamier’s death is that he died during Allied bombing raids. Supposedly, the details were provided by a “secret and reliable source.” To this day, Frank Chamier, the only MI6 agent to fall into the hands of the Germans, is still classified as “missing” and the family has never officially learned of his fate despite numerous attempts to find out the truth.

British Custody

Almost immediately after his capture, the British concluded that Kopkow’s knowledge of Soviet intelligence and his contacts would be useful to them. The world war was in the rearview mirror and the new threat to the Americans and British was the Soviet Union. German counter-intelligence techniques and expertise on the Communist networks led the two Allied countries to scoop up and protect former Nazis they believed could assist with their secret intelligence efforts against the Soviets. (Click here to read the blog, Hang ‘Em or Hire ‘Em.) Nazi killers, including Kopkow, were protected from war crimes trials where they would have been held responsible for their actions during the war.

The British considered Kopkow to have an “encyclopedic” knowledge of the German intelligence system and Kopkow knew immediately that his knowledge would save his life if used properly. He began to cooperate with his interrogators offering up information typed up in voluminous reports by his former secretary, Bertha Rose. In June 1947, the former Paris SS-Sturmbannführer and a direct report to Kopkow, Hans Kieffer (1900−1947), stood on the trap door of the execution gallows and repeated he had acted under direct orders of his boss. Kopkow had previously been held by the Allied War Crimes Group for suspicion of ordering the executions of foreign agents, allied airmen, and British POWs. However, Kopkow was released for provisional “special employment” by an “I” agency (i.e., intelligence) with the understanding Kopkow could be prosecuted in the future.

After evidence made it clear that Kopkow had ordered the executions of women SOE agents, the War Crimes Group wanted him back. By now, Kopkow was an agent for MI6, and they could not afford to lose him. The war-crimes case against Kopkow was closed after MI6 issued a letter stating he was dead. A fake death certificate was produced, and their man was issued a new identity as “Peter Cordes.” Horst Kopkow was never brought to justice for his crimes.

Post-War Career

It is rather sketchy as to Kopkow’s MI6 role after 1948. He returned to his family in 1950 and Gerda recalled he suddenly appeared and announced his new identity. He was introduced to her friends as “Uncle Peter.” His cover was working as the factory director for a local textile manufacturer. For the next six years, Kopkow (Cordes) traveled quite extensively overseas. No one can say how long Kopkow worked for British intelligence or what services he performed. His family has written to government agencies asking for information but has never heard back. Before his death, Kopkow destroyed all his personal papers. It is likely he was used to build up spy networks inside the eastern bloc during the 1950s.

By 1956, Kopkow took back his former name calling himself, Horst Kopkow-Cordes and his time with the SIS was probably up by then. According to Gerda, no questions were asked in Germany as so many others had similar reasons to change names, disappear, or go underground. During an interview, Gerda admitted that her husband knew what was happening at the concentration camps. One thing is clear. British intelligence protected Kopkow for the rest of his life. He was never asked to give evidence at subsequent war-crimes trials and MI6 continued to sanitize his story. Kopkow’s role in executing SOE agents was withheld from the SOE’s official historian, M.R.D. Foot and he stated, “The efforts I made over 40 years ago to inquire who in the SS had ordered the murders of captured SOE agents were blocked. I got nowhere and gave up.”

Many of Kopkow’s direct reports, agents, and colleagues were executed for war crimes including carrying out the orders of Kopkow to eliminate opponents of the Third Reich. Kopkow was a desktop murderer whose pen signed the orders for “Special treatment” of hundreds of foreign agents including the men and women who were former colleagues of Kopkow’s employer and protector, the British SIS.

Horst Kopkow died of pneumonia in 1996 surrounded by his family.

Next Blog: “Don’t Read This”

Correspondence and Commentary Policy

We welcome everyone to contact us either directly or through the individual blogs. Sandy and I review every piece of correspondence before it is approved to be published on the blog site. Our policy is to accept and publish comments that do not project hate, political, religious stances, or an attempt to solicit business (yeah, believe it or not, we do get that kind of stuff). Like many bloggers, we receive quite a bit of what is considered “Spam.” Those e-mails are immediately rejected without discussion.

Our blogs are written to inform our readers about history. We want to ensure discussions are kept within the boundary of historical facts and context without personal bias or prejudice.

We average about one e-mail every two days from our readers. We appreciate all communication because in many cases, it has led to friendships around the world.

★ Read and Learn More About Today’s Top ★

Breitman, Richard, Norman J.W. Goda, Timothy Naftali, and Robert Wolfe. U.S. Intelligence and the Nazis. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

Breitman, Richard and Norman J.W. Goda. Hitler’s Shadow: Nazi War Criminals, U.S. Intelligence, and the Cold War. Washington D.C.: National Archives, 2010.

Delarue, Jacques. The Gestapo: A History of Horror. Yorkshire, U.K.: Frontline Books, 2008.

Foot, M.R.D. SOE in France. London: Whitehall History Publishing, 2000. Original publication by HMSO in 1966.

Helm, Sarah. A Life in Secrets: Vera Atkins and the Missing Agents of WWII. New York: Anchor Books, 2007.

Jacobsen, Annie. Operation Paperclip: The Secret Intelligence Program That Brought Nazi Scientists to America. New York: Back Bay Books, 2014.

Jeffery, Keith. MI6: The History of the Secret Intelligence Service 1901−1949. London: Bloomsbury, 2010.

McDonough, Frank. The Gestapo: The Myth and Reality of Hitler’s Secret Police. New York: Skyhorse Publishing, 2017 (first edition published in London by Coronet Books, 2015).

Nelson, Anne. Red Orchestra: The Story of the Berlin Underground and the Circle of Friends Who Resisted Hitler. New York: Random House, 2009.

O’Reilly, Declan. Interrogating the Gestapo: SS-Sturmbannführer Horst Kapkow, the Rote Kapelle and post-war British Security Interests. Journal of Intelligence History. Routledge: 1-24., 2021.

Saward, Joe. The Grand Prix Saboteurs. London: Morienval Press, 2006.

Tyas, Stephen. SS-Major Horst Kopkow: From the Gestapo to British Intelligence. Stroud U.K.: Fonthill Media, 2017.

Walters, Guy. Hunting Evil: The Nazi War Criminals Who Escaped & the Quest to Bring Them to Justice. New York: Broadway Books, 2010.

This blog is only a snapshot of Horst Kopkow’s story (at least the story that can be supported by interviews and declassified documents). Stephen Tyas has written an excellent book about Kopkow and it is superbly researched. I recommend you read his book for a more complete accounting of Kopkow’s career as a Nazi war criminal and his subsequent employment by the British SIS.

Disclaimer:

There may be a chance that after we publish this particular blog, the video links associated with the blog are no longer accessible. We have no control over this. Many times, whoever posts the video has done so without the consent of the video’s owner. In some cases, it is likely that the content is deemed unsuitable by YouTube. We apologize if you have tried to access the link and you don’t get the expected results. Same goes for internet links.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

Several of the highlights of our trip to Holland and Belgium were stops in the south at the delta works and Arnhem. It was a miserable day weather wise when we traveled to see the massive dikes and made-made dams keeping the waters of the North Sea from flooding the lowlands. We stopped at the Watersnoodmuseum which is the “National Knowledge and Remembrance Center for the Floods of 1953.” The museum is housed in four caissons used to close the last gap in the dike. The Phoenix caissons were part of the Mulberry Harbor in Arromanches-les-Bains and used by the Allies to unload supplies after D-Day on 6 June 1944. More about the museum and caissons in our 1 July 2023 blog, “Mulberry Harbor and the Delta Works.”

Our stop in Arnhem was centered around “Operation Market Garden.” We began by visiting the Hartenstein Hotel in Oosterbeek. The mansion was used by the British 1st Airborne Division as Major-General R.E. Urquhart’s headquarters during the mission. We saw the British and American landing fields for the airborne troops as well as gliders and supplies. Along the way were numerous memorials commemorating the battle but the most moving was the visit to the Arnhem Oosterbeek War Cemetery, otherwise known as the Airborne Cemetery. The cemetery is administered by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission and contains the graves of about 1,770 Allied men who perished during the battle (primarily men from the U.K. and Poland). It is a battle I have never studied, and I hope to go back at some point with a little more knowledge than having watched the movie “A Bridge Too Far.”

Thank you to all of you who subscribe to our bi-weekly blogs. It seems there isn’t a day that goes by where we don’t increase our readership. Please let your history buff friends and family members know about our blog site and blogs.

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

Thanks to John R. for contacting us. John wanted to know how we came up with the name “Yooper” for the publishing company. Well, my father was born and raised in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan and the folks up there are affectionately called “Yoopers.” And there you have it. Thanks, John, for asking and I appreciate you mentioning the Gestapo book.

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Do you enjoy reading? Do you have a hard time finding the right book in the genre you enjoy? Well, Ben at Shepherd.com has come up with an amazing way to find that book.

Shepherd highlights an author (like me) and one of their books (in our case, it is Where Did They Put the Gestapo Headquarters?). The author is required to review five books in the same genre. So, if a reader is interested say in cooking, they can drill down and find specific books about cooking that have been reviewed by authors in that category. Very simple.

If you like to read, I highly recommend you visit Shepherd.com. If you do, please let me know what you think and I will forward Ben any suggestions or comments you might have.

Click here to visit Shepherd’s website.

Click the books to visit Stew’s bookshelf.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and Apple Books.

Please contact Stew directly for purchase of books, Kindle available on Amazon. Stew.ross@Yooperpublications.com or Contact Stew on the Home Page.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Walks Through History

Copyright © 2023 Stew Ross